By André Blais, Eric Guntermann & Marc A. Bodet

What is the story?

We propose a simple and original standard for evaluating the performance of electoral democracies: the degree of correspondence between citizens’ party preferences and the party composition of the cabinet.

The criteria

We propose three criteria for assessing the correspondence between citizens’ party preferences and the party composition of governments that are formed after elections:

- The proportion of citizens whose most preferred party is in government

- Whether the party that is most liked overall is in government

- How much more positively governing parties are rated than non-governing parties

The data

We use CSES data that include a party like/dislike question in which respondents are asked to rate each party on a 0-10 scale.

We focus on lower house elections in non-presidential democracies. Our sample includes 87 legislative elections held in 35 countries. We distinguish elections held under PR and under non-PR, and on the basis of disproportionality between vote and seat shares. For each party we compare its ratings in the electorate and the proportion of seats it had in the cabinet that was formed after the election.

Results

Criterion 1: How many citizens have their preferred party in government?

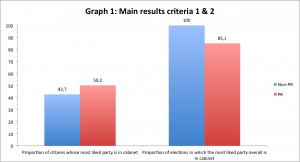

More people have their preferred party in government under PR, and this is due to the fact that PR leads to the presence of more parties in cabinet. As is shown in Graph 1 below, 50% of citizens, on average, get their most liked party in government under PR, compared with 43% in non-PR elections. On this first criterion, PR elections perform better.

Criterion 2: Is the most liked party in government?

We compute the mean ratings of all the parties in each election to identify the party that is most liked overall and determine whether that party is in government or not. The most liked party was in government after each of the ten non-PR elections, while that was not always the case following PR elections. Namely, in 11 PR elections out of 74 (15%), the most liked party found itself in the opposition. On this second criterion PR elections perform worse.

Criterion 3: Are governing parties better liked than non-governing parties?

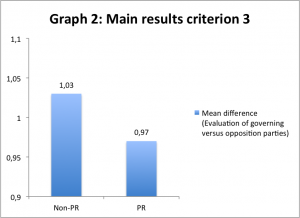

Governing parties are better liked than opposition parties in 82 of the 87 elections. But the mean differential, as can be seen in Graph 2, is slightly more positive in non-PR elections. This is so because PR elections usually lead to the formation of coalition governments that often include at least one small party, and small parties are usually less liked than large parties. On this third criterion PR elections also perform worse.

Conclusion

Coalitions formed under PR lead to the inclusion of more citizens’ most liked parties in government (which is good) but they also allow small less liked parties to enter government (which is not so good). In short, before concluding that one system is better than the other we must decide which aspects of citizens’ preferences matter the most.

For more details, see André Blais, Eric Guntermann, and Marc André Bodet. Forthcoming. « Linking Party Preference and the Composition of Government : A New Standard for Evaluating the Performance of Electoral Democracy. » Political Science Research and Methods.