By Valérie-Anne Mahéo, McGill University

What is the story?

In Canada, as in other industrialized democracies, low and declining turnout rates among youth have become a central democratic problem. This problem is especially acute among disadvantaged and less educated youth, who are less likely to vote than the rest of the population.

In this blog post, I present a civic education activity that was conducted by the MEDW project and the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship1 , in collaboration with the NGO Apathy is Boring. This activity took the form of a voting game. The goal was to raise the awareness of less educated and under-privileged young Canadians about several issues related to elections.

The voting game

Between the summer of 2013 and the summer of 2014, we organized 20 workshops in the province of Quebec. These workshops reached close to 300 disadvantaged or unemployed young people. The participants were aged 18 to 30 and were taking part in youth employment or training programs. The workshops lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours.

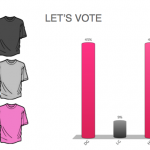

The participants played the voting game in small groups of 9 to 16 people. They were told that they were part of a soccer team that has to decide the color of their jerseys (black, grey or pink). This decision was made through a vote with clickers and the results were directly projected on a screen. Each participant had one vote. The winning color was the color that obtained the most votes. In each workshop, we organized 6 rounds of vote (see Picture 1). The first three rounds were played in silence, while the participants could communicate with each other during the last three.

|

|

|

Picture 1: Excerpt of the instructions (click to enlarge)

Each participant was given a set of ordered preferences for colors (with a most preferred and least preferred color). If the group elected the preferred or second preferred color of a participant, he/she received points (more if his/her preferred color won). At the end of the game, we calculated all the points obtained in all the votes. The ultimate goal for the participants was to win the most points: the more they had points, the more chances they had to win free movie passes.

The ‘groups with preferred colors’ were uneven and some had different orders of color preferences. Therefore, the participants had incentives to think strategically about their vote. It was sometimes better (in terms of winning points) to vote for their second preferred color. We believed this would raise their awareness about elections and the multi-facets strategies of the vote.

The participants’ feedback

After the voting game, participants were offered to share their impressions. Many participants said that they did not realize there were different ways of voting and hadn’t thought about voting ‘strategically’ before. Conversations usually broadened and participants discussed elections and voting more generally (see Picture 2). While these youth were typically disengaged, they were not apathetic about politics and had lots to say on the matter.

These workshops elicited meaningful dialogues about politics and democratic participation. They were lively and interesting with a small number of youth going so far as to encourage their peers to vote for their favorite political party. Few youth however said they would vote in the next election.

While the voting game was effective in teaching youth about the different ways to vote, it was not very effective in mobilizing them to vote. This result is in line with past research that has shown that one single civic education activity may not be enough to stimulate a change in political behaviour. However, the immediate repercussions of these workshops reinforced the positive message of civic engagement. Typical remarks from the employment centers’ coordinators were that of excitement and optimism. They were grateful to have their youth participate in discussions on topics that are not usually addressed in their training or employment programs.

The researchers involved were André Blais (University of Montreal), Elisabeth Gidengil (McGill University), Valérie-Anne Mahéo (McGill University), Sara Vissers (McGill University), and Carol Galais (University of Montreal). ↩