By André Blais, Full Professor at the Université de Montréal

http://www.crcee.umontreal.ca/director_a.html

What is the story?

The United States have untypical electoral institutions. Many features are at odds compared to other world democracies: the usage of the first past the post (FPTP) system and primaries, the decentralization of electoral administration, the very short terms of office, and partisan redistricting. In this piece, I contend that while experts (i.e., specialists in comparative study of political institutions) evaluate these institutions negatively, US citizens are rather satisfied with the way it works in their country. I suggest some reasons for this divergence of opinion. I consider that experts are right and people are wrong.

Expert evaluation

Most of the experts believe that FPTP is not a very good system. In a recent study, Bowler, Farrell, and Pettitt (2005) asked international scholars in the field to rank order various types of electoral systems. FPTP came out six out of nine in mean rank, way behind other systems. As a matter of fact, very few democracies keep using FPTP. Only the UK, Canada and a handful of former British colonies have not managed to get rid of it.

The system used to elect the American President is even worse. No other contemporary democracy elects its president through electoral colleges. The few electoral colleges that existed, such as in Argentina and Taiwan, have been abolished. Among experts, this system is unanimously viewed as “dépassé” and unacceptable in a democracy.

The frequency of elections is also questionable. An overwhelming majority of first chambers in the world have four or five year terms. The two year term for the House of Representatives is extremely short, Most international experts would agree that two year terms are “crazy”.

Let’s talk about the decentralization of electoral administration. Canadians and Europeans were stunned to learn, during the 2000 presidential election mess, that fundamental decisions as the right to vote vary from one state to another. There is indeed no federal electoral law in the US. As far as I can tell, only Switzerland is in such a situation. The fact that a state legislature can decide who is allowed to vote in a federal election, in a country which is relatively centralized on most accounts, is absolutely weird.

There is another aspect where US practice appears exceptional: the drawing of constituencies. In most contemporary democracies, the drawing of constituency boundaries has been delegated to independent commissions, while this is under politicians’ control in the great majority of American states. Clearly politicians are in a conflict of interest here.

However, it has to be acknowledged the U.S. may be construed as “avant-garde” in terms of party primaries. It is the only country in which almost all party nominations are made directly or indirectly by voters. In many countries there has been a clear movement for opening the nomination process to a wider electorate.

On almost all fronts (the primaries being the only exception), U.S. electoral institutions are weird.

Citizen evaluation

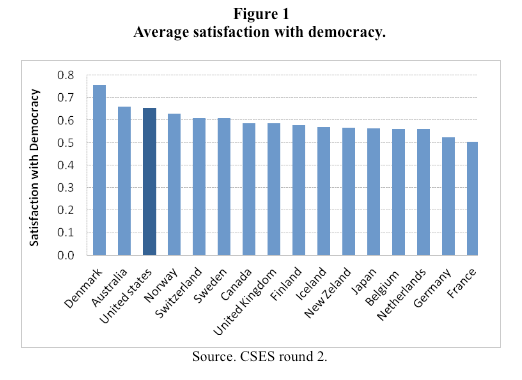

American citizens have a very different opinion about the country’s electoral institutions. They appear to be very satisfied with the way democracy works. Figure 1 presents the mean score obtained to the question “on the whole, are you very satisfied (1), fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied (0) with the way democracy works in (country)? » in 16 established democracies (CSES data, round 2). The US scores quite high on this dimension. It comes clearly ahead of the UK, France, and Germany.

A second indicator is losers’ consent. A democratic election is bound to produce winners and losers. The hope is that losers will accept an outcome that they dislike, that is, they will recognize that the outcome is legitimate because the process through which the winner was designated was a fair one. The 2000 US presidential election certainly fits the bill of a “difficult” election. Gore has more votes yet he loses. There are serious doubts about how the votes are counted in Florida. The whole issue goes before the courts and takes weeks to be resolved. The final decision is made by the courts and the judges are divided along partisan lines. All this is awful. Yet in the end the Democrats graciously accept defeat.

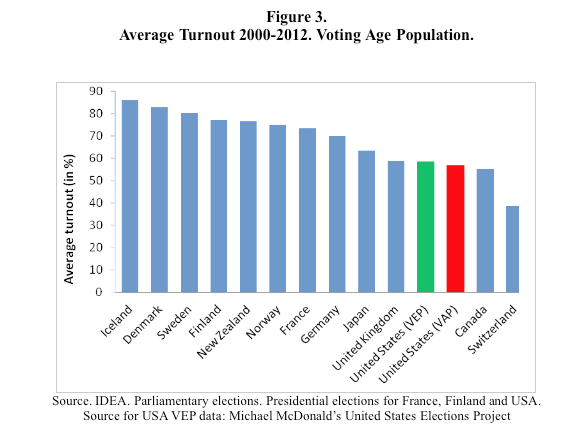

A third indicator is turnout. Much is made of the fact that turnout (measured in terms of voting age population) is low in the U.S. (see Figure 2). But it is similar to that observed in other large democracies like Japan and the UK and only slightly lower than in France and Germany. If we take into account that registration is more difficult than in most other countries, that people are more mobile, and that there are far too many elections, the conclusion that turnout is low in the U.S. must be revisited. In short, turnout is not exceptionally low in the U.S. In fact it is relatively high given the extra hurdles imposed by the registration process and the exceptional mobility of its citizens.

Conclusion

American electoral institutions are in many ways exceptional. Except for primaries, these institutions are construed to be “bad” by experts. So why are Americans so satisfied? My hypothesis is that their tolerance for malfunctioning institutions is high because patriotism is so strong. When you feel that you live in a great country, you are more willing to accept “deficiencies”. The culprit, I suggest, is blind patriotism. Americans are very proud of being Americans, more so than Canadians and Europeans, and this makes them unable to see that their electoral institutions are in a very bad shape.

For more information, see Blais, André. 2013. “Evaluating US Electoral Institutions in Comparative Perspective.” In Jack H. Nagel and Rogers M. Smith (eds), Representation: Elections and Beyond. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

2 Comments

Thanks Sona!

Nice post - just in time for a new semester! I think this could be useful reading for the students in my comparative politics courses.